Climate Emergency Declarations Accelerating Decarbonisation? What 249 UK examples can tell us.

Calum Harvey-Scholes, IGov Team

20th September 2019

Introduction

Following the IPCC 1.5oC Special Report in October 2018, it is clearer than ever that we need to accelerate decarbonisation policy at every level to limit global heating. We know that more than half of all anthropogenic carbon emissions have occurred in the past 30 years, since the establishment of the IPCC, and global carbon emissions are still climbing every year.

The IPCC report, the school climate strikes, Extinction Rebellion, and Climate Change: The Facts with David Attenborough have all contributed to raising awareness of the climate crisis across the UK. People have been calling for action and collaborating with their local politicians via local organisations, such as extinction rebellion groups, to push the climate crisis up the local political agenda in what has become a broad-based movement for local action. This has prompted a recent and growing trend of organisations, particularly local government, declaring a ‘Climate Emergency’ (CE). The aim of this people-based pressure is to push local governments to take action to reduce carbon emissions as well as put pressure on national government.

Figure 1 – A map of Climate Emergency declarations across Europe as of July 2019.

IGov has studied 237[1] UK local authorities which have declared a climate emergency in order to understand how this movement is driving decarbonisation policy. This blog 1) outlines some observable features of these declarations, 2) suggests some initial groups among them; and then 3) looks at four ways in which these declarations are transforming, and potentially accelerating, local decarbonisation by:

- Setting a new, accelerated deadline for a local carbon reduction target.

- Establishing local authority ‘Climate Action Plans’.

- Using local authorities’ soft power to engage local communities with decarbonisation.

- Calling national governments to provide power and resource to take action locally.

1 The declarations in numbers

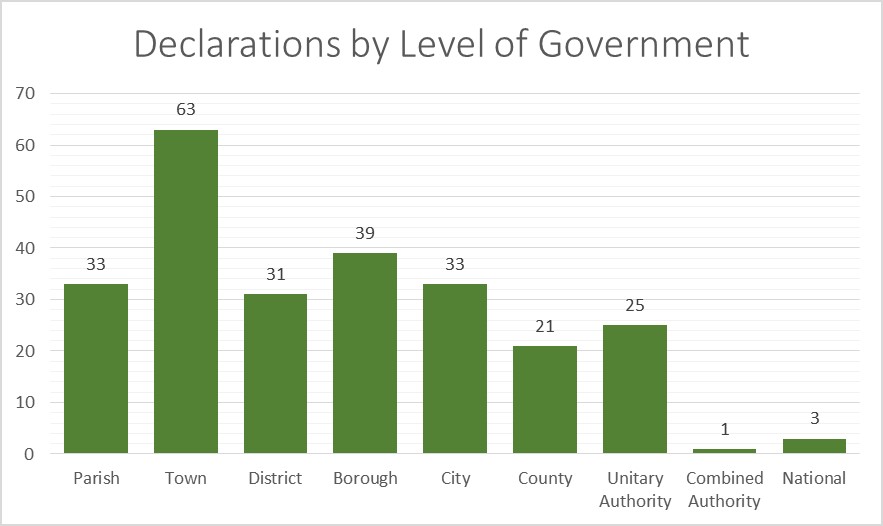

Governments across a range of levels have declared a CE in the UK, from parish councils’ up to devolved national governments – Figure 2.

Figure 2 – Local authority climate emergency declarations by level of government.

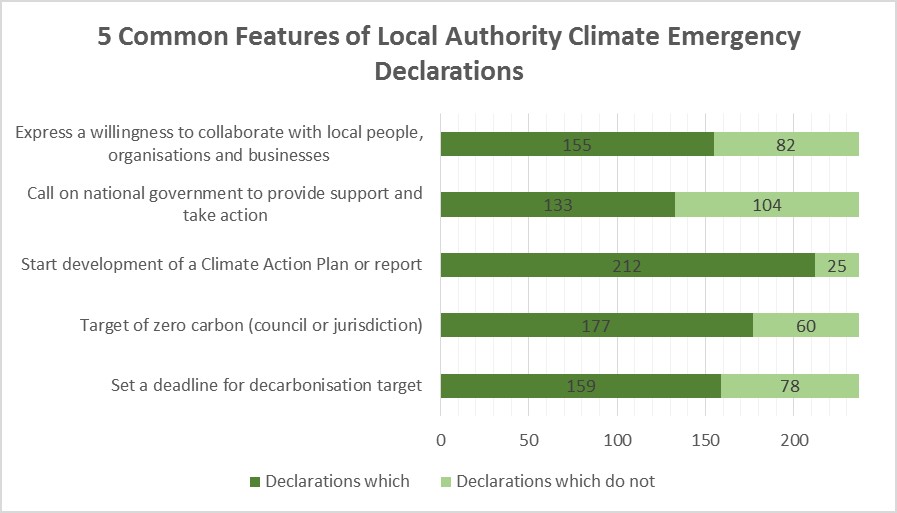

Across the 237 CE declarations with information, there are five common features which appear in many of the declarations which are shown in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3 – Five common feature of local authority climate emergency declarations, based on analysis of the written declarations.

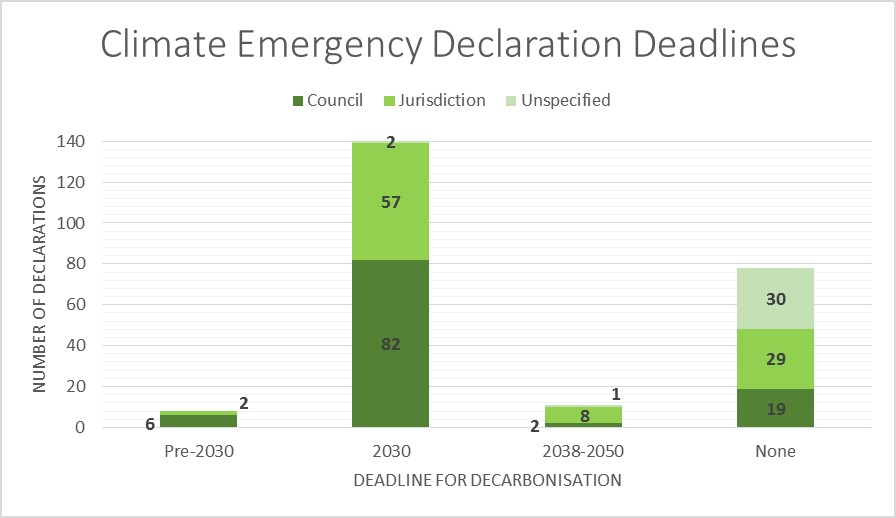

A central element of most (159, 67%) of the CE declarations is a deadline for decarbonisation. These range from 2023 to 2050, but the majority aim for 2030. Where specified, the scope of decarbonisation includes the whole jurisdiction or the council’s activities. Council activities includes elements like the councils’ buildings, energy use and vehicle fleet which are used or owned by the council for administration or delivering services like waste collection. Analysis of Government regional emissions reports and local authority self-reporting data for 114 local authorities suggests that the direct emissions from these activities generally account for less than 5% of the emissions in the whole jurisdiction of the local authority. For those declarations which aim to achieve carbon reductions across the whole jurisdiction, this is assumed to include all activity by individuals, organisations and businesses, such as travel, electricity use, food, heating and buying any kind of product. 31 of the declarations which have a target for the jurisdiction explicitly refer to ‘both production and consumption emissions’.

Figure 4 – Local Authority Climate Emergency Decarbonisation Deadlines broken down by deadline date and by the scope of decarbonisation.

2 Types of declaration

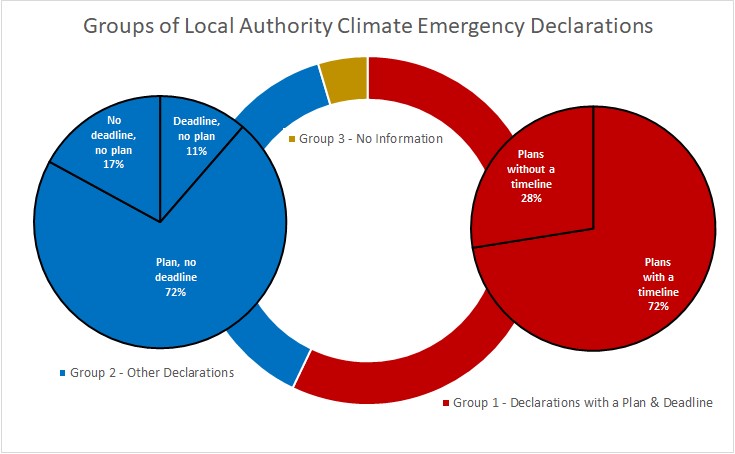

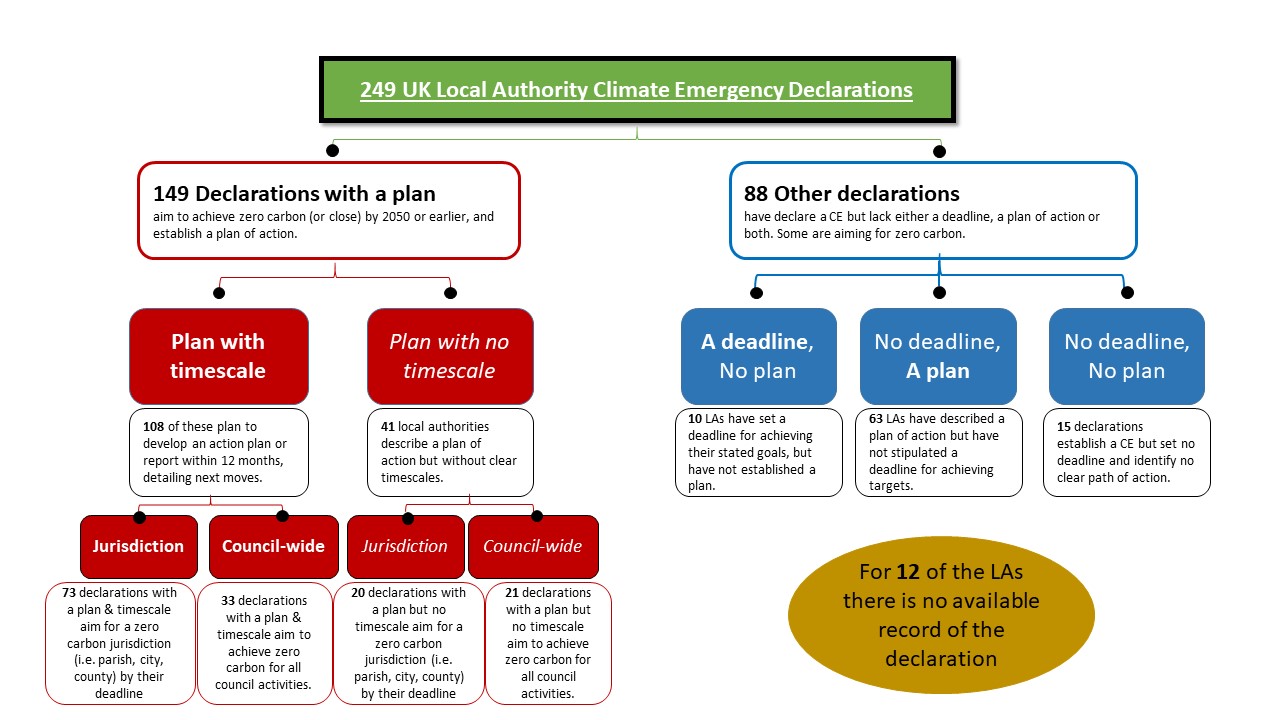

The declarations studied here could be divided in a variety of ways. The focus of this research is on accelerating policy for decarbonisation and therefore it makes sense to separate those with explicit and time-bound plans of action from the rest. Two major groups are identified: Group 1 contains 149 local authorities (60%) whose CE declarations set out a plan and have a deadline for decarbonisation, and Group 2 comprises 88 other declarations (35%) – those which lack a plan, a deadline, or both. A third group (Group 3) contains 12 local authorities (5%) reported to have declared a climate emergency but about which there is no discoverable information.

All declarations in Group 1 set the development of a plan in action, 72% of these also set a deadline for a report back to the Council. 72% of the Group 2 declarations have a plan but no deadline, 11 have a deadline but no clear process for making a plan, and 17% lack both. This is broken down in Figure 5.

Figure 5 – Grouping Local Authority Climate Emergency declarations by those with a plan and deadline, and those without either a plan or a deadline, or with neither. Those with both a plan and a deadline are then broken down on the right into those with a timeline for the plan stated in the declaration, and those without.

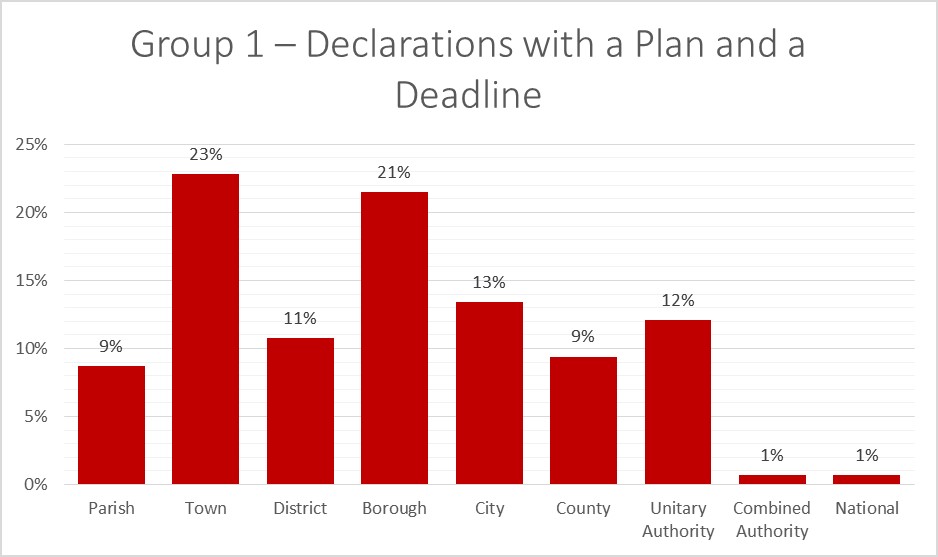

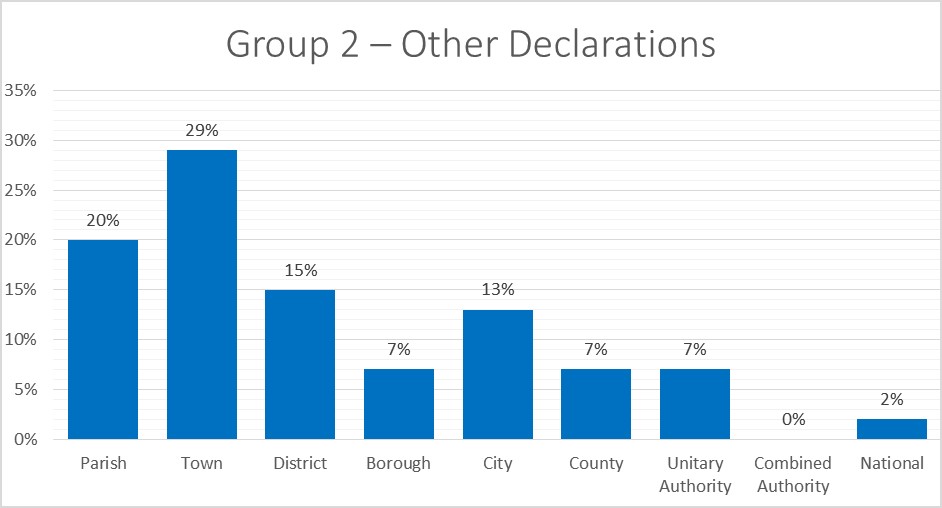

These two groups (those with both a plan and a deadline (Group 1), and those lacking either or both (Group 2)) include local authorities across the levels from parishes up to devolved national governments. However, Group 1 has a lower proportion of parish, town and district councils, and a higher proportion of borough, county, unitary authorities and combined authorities. Using UK census and population projection data from the Office National Statistics, we estimated the population in the jurisdiction of each local authority. Group 1 local authorities tend to cover larger populations, with a median population of 129,000 people, compared to a median population of 52,741 people for Group 2. That is to say that, in general, larger councils appear to be making more explicit, concrete plans.

Figure 6 – The percentage of Group 1 made up by local authorities of each level

Figure 7 – The percentage of Group 2 made up by local authorities of each level

Groups 1 and 2 can be helpfully broken down further into a hierarchical typology as laid out in Figure 8.

Figure 8 – A hierarchy grouping UK local authority climate emergency declarations.

3 Four Ways Local Authority Climate Emergencies are Accelerating Decarbonisation

Local Authorities’ Remit

Action to tackle climate impacts locally is relatively fragmented across areas, such as planning, transport, and waste. The Local Plan is the basis for planning and development locally and has a legal obligation to reduce carbon (ClientEarth, 2019), but the degree to which this is prioritised or enforced often depends on the individual council. Local authorities can also facilitate retrofitting renewable energy generation like solar PV, for instance, by organising collective buying schemes or community ownership. At the parish level, neighbourhood plans are also a powerful way for people to collectively steer local development.

With transport, local bus services and road building are under the control of top tier local authorities (e.g. county councils). Air pollution has pushed reducing traffic up the agenda in some urban areas. But transport is not always treated as climate-relevant, with new by-passes, rather than improved public transport, often preferred as a solution to ‘alleviate’ traffic.

Local authorities have responsibility for waste disposal and levels of recycling have increased over recent decades. Across the UK as a whole, annual increases in the proportion of waste recycled have stalled over the past five years (DEFRA, 2018).

Many local authorities own farms, forests, parks and green spaces, these are all potential carbon sinks and wildlife habitats. Carbon sequestration can be employed either (A) to absorb previously emitted carbon already in the atmosphere and reduce our existing carbon debt, or (B) to ‘offset’ continuing carbon emissions being added to the atmosphere, not reducing the carbon debt.

Setting an accelerated deadline for a carbon reduction target.

159 (64%) of the CE declarations establish a commitment or ‘aim’ to achieve zero carbon by a particular date. Some are more ambitious than others – the dates range from 2023 to 2050, and the scope varies from all council operations to the entire jurisdiction – but importantly, and for the first time in almost all cases, these local authorities establish a target (zero carbon, or close) and a deadline for emissions reduction.

UK local authorities do not have explicit statutory carbon budgets or deadlines placed on them, for their own operations or for their jurisdiction, and so until last year very few had adopted specific targets for zero carbon with firm deadlines. The idea of local carbon budgets is not new and has been discussed in the UK for more than 8 years, without being implemented. At IGov, we think that they could be an effective way to devolve national carbon budgets.

Climate Action Plans

The vast majority (212, or 89%) of the local authority CE declarations set in motion the development of a ‘Climate Action Plan’ or a report detailing what action on the CE means in practice. This is an opportunity for local authorities to begin holistic planning for climate action and engagement across all areas. The development of a local Climate Action Plan provides the perfect opportunity to work across council departments, as well as between local council layers (such as towns, cities and districts, and county) to collaboratively design an integrated plan of action across all the areas mentioned above. There are at least three aspects which help effectiveness: (1) the development process, and its implementation, should be adequately resourced and not rushed. (2) Local people as well as businesses should be involved in the process. (3) Local authorities should collaborate and share best practice.

Using soft power to bring local communities along.

154 (65%) of the declarations studied mention working locally to collaborate and engage people. Local authorities are well connected and integrated in their communities which means that they have a valuable soft power for engaging local residents to enable meaningful acceptance of the behavioural and social transformations necessary.

Asking national governments to provide power and resource to take action locally.

134 (57%) of the local authorities declaring a CE have also written to the government calling for action, and primarily requesting the provision of powers and resources to enable the achievement of the ambitious CE targets. Central government support is vital for local action as much activity within local authority jurisdictions is not controlled locally.

In planning, Local Plans are bounded by national policy such as the wording of the National Planning Policy Framework. Local authorities are justifiably fearful that imposing stricter energy efficiency standards or other requirements may incur expensive legal costs from developers taking legal action. In this context, ClientEarth’s recent announcement underlining local authorities’ legal obligation to prioritise climate action in Local Plans could be taken in the spirit of a supportive, expert friend, encouraging local authorities to be more demanding.

With transport, major highways and rail connections are beyond the control of local authorities and change in line with the demands of the CE would require action from central government.

For waste, the same goes for regulating the sale of unreusable or unrecyclable products or packaging – action upstream of waste processing needs a broad approach from central government.

4 Conclusion

The CE declarations studied here appear to increase the ambition of local authorities with regard to decarbonisation, many of them setting explicit goals and target dates. However, this ambition needs to be followed by concrete action, and there remain questions about the ambition of some, such as those declaring a CE without a plan or a deadline.

More broadly, CE declarations from many local authorities have been a powerful way to send a clear, collective message from people and local politicians across the UK to central Government calling for accelerated action to decarbonise the country. The ambition that is emerging at the local level will become increasingly important in enabling the UK to decarbonise at the pace required. It will also directly support the Committee on Climate Change advice for enabling the UK to become net zero by 2050, now enshrined in law through the 2008 Climate Change Act. As such central governments should support the actions of local authorities and take responsibility for the direction and co-ordination required to deliver comprehensive, rapid decarbonisation.

[1] 249 reported declarations were studied in total, but for 12 no information could be found.

Related Posts

« Previous Submission: BEIS / Ofgem Consultation on Flexible & Responsive Energy Retail Markets Submission: Environmental Audit Committee Inquiry into Net Zero Government Next »