The empire strikes back – first capacity auction outcomes

The empire strikes back – first capacity auction outcomes

Matthew Lockwood, IGov Team, 26 Jan 2015

About Matthew: http://geography.exeter.ac.uk/staff/index.php?web_id=Matthew_Lockwood

Twitter: https://twitter.com/climatepolitics

As regular readers of the IGov blog will know, one of our favourite topics is the capacity market – see here, here and here – probably because it is such a clear demonstration of how governance of the UK energy system can act to impede change in the direction of a more sustainable system. Now the results of the first capacity market are in, the dust is settling, and it is beginning to become clear what has gone wrong and why.

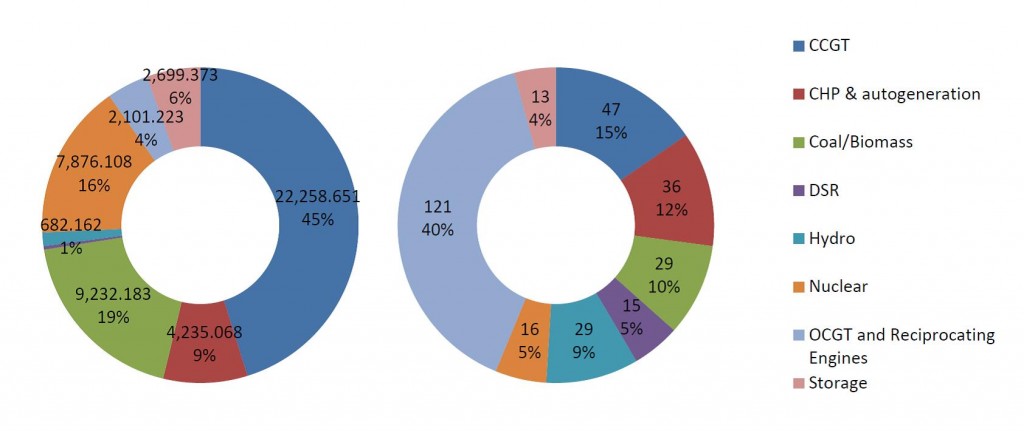

The first auction concluded on 18 December 2014. It is a T-4 auction, meaning that it is for delivery of capacity availability from 2018. Just short of 50GW has won contracts, at a clearing price of £19.40/kW. The technology mix of those bids that cleared the auction is shown below: the relevant bit is the left hand pie chart which shows capacity.

The first point, made by many observers, is that the CM (and ultimately electricity consumers) is now paying to extend the lives of 9.2GW of old coal-fired power stations. This flies in the face of decarbonisation policy (especially given the freezing of the carbon price support), and squeezes out other technologies.

A second point, picked up sharp eyed analysts at Cornwall Energy (paywall), is that (some of) the Big Six energy companies have done very well. Of total capacity payments for 2018 of £955 million (2012 prices), Big Six companies will receive 74%. As Cornwall Energy note, “it is hard to see how this makes room for new players to enter the market”.

If the auction has propped up old high carbon technology and consolidated the financial position of the incumbents, it has also done very little in practice for a source of capacity that should be playing a more important role, i.e. demand side response (DSR). The government assured participants that the market was being designed to offer fair access for DSR, and it was allowed to be a price maker and bid in up to the clearing price, but as things worked out, DSR is playing such a marginal role that you can hardly see it in the diagram above.

Why is this? Firstly, there were problems in prequalification, with a lot of effectively proven DSR having to prequalify as unproven and therefore incur extra costs such as posting bid bonds. DECC seem to have been unresponsive to efforts to clarify problems by the DSR industry, relative to their desire to make sure things worked for the large generating units. As in other areas of policy, the complexity of entering the auction means high fixed costs of participation. This not only deters small actors but also makes aggregation more difficult. It seems that the government often expects aggregation to be the answer to many questions about how smaller actors can participate in UK markets, and that aggregation will happen automatically, but it rarely designs markets in such a way as to help hat happen, indeed the reverse. Overall, it certainly looks as if the capacity mechanism wasn’t designed to develop DSR.

But the outcome also brings back into focus the question of what the original purpose of the CM was and how this first set of results fits with that stated purpose. One apparently important driver for the CM was a need to address the expected a supposedly critical squeeze on capacity margins, with a lot of media attention on the winter of 2015/16. Yet the 2014 auction and another one in December 2015 will do nothing at all to help that situation – because they won’t deliver capacity availability until 2018. Presumably this leaves the system operator relying on strategic reserve to manage the winter of 2015/16, which was one of the original options back in 2011. It is not wholly clear why this approach couldn’t simply be maintained instead of a CM. DECC and Ofgem capacity margin projections do show some deterioration after 2018, but the margin curve is always downwards sloping over time. Bringing in a new capacity market would only be justified if things had really changed.

The argument is of course that they have, and that the other driver of the CM is the need to subsidise relatively infrequently used flexible plant or DSR to cope with increasing amounts of intermittent wind that we are expecting (or perhaps not?) as we move towards and into the 2020s. But in that case why do we have 7GW of nuclear cleared from 2018 onwards? Though nuclear is flexible in theory, it is costly to ramp up and down in practice, and it is hard to see nuclear ever winning in an auction for flexible capacity, as opposed to brute megawatts.

A final point is that the cheapest way of keeping the lights on would be demand reduction through greater energy efficiency. Energy efficiency plays a significant role in deferring generation investment in some US electricity markets, such as the PJM. Here, the government has set up an Electricity Demand Reduction pilot to see if a similar role for energy efficiency in the capacity auction could work. Given the potential, the £20 million committed seems rather derisory (and some take the view that the EDR was a sop to critics who wanted an energy efficiency feed-in tariff). However, the main problem is the timing. While the EDR is trundling at a minor scale, the December 2014 auction has already underwritten the construction of 2.6GW of new generating plants, and there may be more to come in the 2015 auction. The more logical thing to do would have been to have a much more ambitious fast-tracked EDR pilot before embarking on an auction, and potentially avoiding unnecessarily subsiding new power stations.

Overall, the CM looks like it has met the expectations that it would be backward looking in terms of carbon and incumbency. Its almost exclusive focus on the supply side does little or nothing for the development of a future energy system. This looks very much like a case of vested interests winning out. You would expect the Big Six to press for a market design that benefits them, and most have indeed done well (National Grid will also be welcoming the fact that the CM increases demand for transmission). The real question is why the government has allowed such an outcome, and this will be the focus of an IGov case study. Watch this space…

Related Posts

« Previous New Thinking: Rethinking the role of energy – the Labour 14th January debate New Thinking: We need Board Quota’s for Women in Energy Next »