Governance for local energy transformations

Jess Britton, IGov Team, 3rd July 2019*

It is an understatement to say that there has been a refocussing on local level coordination in energy system change. I have written before about the momentum at this scale, as well as the renewed attention of Local Enterprise Partnership (LEPs) and emerging Local Industrial Strategies in this area. There has also been the announcement of major demonstrator funding for smart, local energy systems via the Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund. But despite these developments there remains a significant mismatch between activity at this scale and governance structures to enable and support change. To address this we propose a new statutory duty on local authorities and the devolution of carbon budgets. Neither of these proposals are necessarily ‘new’ but a range of changes in energy and climate policy – as well as to devolution and spatial planning agendas – mean the time is now right to restructure local-national relationships.

IGov has argued consistently that, in order to rapidly decarbonise, GB energy system governance needs to be overhauled to provide renewed clarity, direction-setting and co-ordination. As we set out here, the problems with the current governance framework for energy system transformation can be summarised as (1) no clear responsibility for carbon reduction, (2) no clear responsibility for demand reduction, (3) no clear responsibility for system integration and (4) ambiguities on social outcomes. We recently outlined our specific proposals on how to develop a fit-for-purpose national governance framework. At the centre of our proposals is the establishment of an Energy Transformation Committee (ETC) to set a strategic direction for energy governance.

The Energy Transformation Commission, a parallel body to the Committee on Climate Change, would be charged with coordinating transformative change, developing political consensus and engaging society in deliberation on key decisions. Of course many aspects of priority setting, policy development, regulatory or market structures and incentives are most appropriately debated and delivered at the national level – and the ETC will play a central role here – but increasingly many of the choices, debates and policies involved in rapid decarbonisation only become meaningful at a more local scale.

My previous blog set out the drivers towards more localised energy systems and the disconnect between evolving technologies, business models, and consumer preferences, and the broader governance system. The new realities of energy systems are increasingly focussed on the distribution level, the local integration of heat, power and transport and engaging people and communities in meaningful ways in what a decarbonised society might look like.

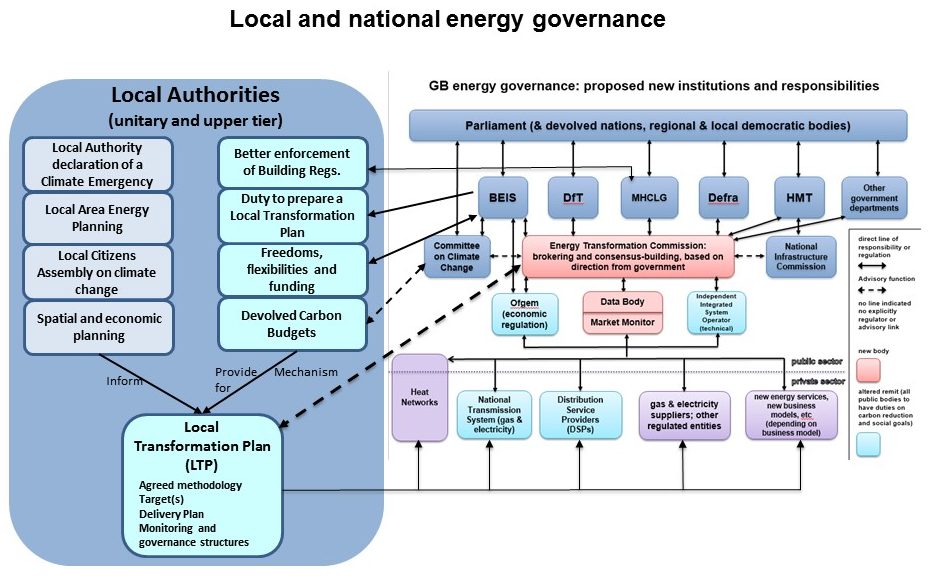

To address this gap we propose the establishment of a statutory duty on local authorities to prepare Local Transformation Plans (LTPs) aligned with the devolution of national carbon budgets to the local level (see the draft framework in figure 1). These plans would build on and formalise much of the current activity at the local level including: the declaration of climate emergencies by numerous councils, the commitment by local authorities (such as Oxford and Camden) to convene local citizens assemblies on climate change (these developments notably taking place at the local authority level before similar commitments were made at the national level), the development of Local Enterprise Partnership energy strategies, the development of five ‘regional’ Energy Hubs to work with LEPs to 2020, Local Industrial Strategies and devolution deals, as well as the myriad of local pilots taking place on elements of energy system change. Importantly these plans would be informed by national guidance on methodologies but go beyond a technocratic assessment of local resources to consider the integration of decarbonisation into strategic local planning, the delivery of co-benefits and local democracy.

Figure 1: Reformed local energy governance framework

While a duty and budgets would be devolved to higher tier local authorities, local areas may choose to develop and deliver plans on a larger scale. Already much strategic planning is taking place at the city regional scale or via Local Enterprise Partnerships and local areas would be best placed to determine the most appropriate governance scale. While such developments are, in principle, about setting requirements on local authorities they do not conflict with the devolution agenda as local areas would not be constrained or directed in terms of how they develop or govern their LTP or deliver local carbon budgets. The government’s commitment to legislate for zero carbon illustrates that action on climate is not on an opt in basis and gone are the days when we could expect some areas to lead the way to a decarbonised society and pick up the slack for the laggards. Clarifying and formalising the local role would provide a forum for bold strategic planning, accelerated delivery, debate with local communities and discussion with central government regarding any further devolution of powers or flexibilities. For example, it is far easier to debate the merits of institutions such as Regional Green Investment Banks if a strong local advocate is in place, backed by a granular understanding of local pipelines of projects and infrastructure needs.

There would also be scope, once a statutory duty and local carbon budgets are established, for local areas to develop local governance structures that align with the work of the national ETC – Local Transformations Commissions in effect. This could both provide a route to build community support for change (incorporating the insights from citizen’s assemblies) as well as coordinating the multiple strategic planning documents local authorities are already preparing – from local plans to neighbourhood plans, local industrial strategies to devolution deals. Importantly, the development of a duty to prepare a LTP would need to tread a fine balance between consistency between areas and avoiding stifling local innovation through too prescriptive requirements. But essentially this is about ensuring that the UK’s net zero target is delivered across the UK, and avoiding the rhetoric and delivery mismatch that has been evident across scales of governance for too long.

In terms of devolved carbon budgets, the Government’s commitment to legislate for a net zero target could provide the opportunity to review the allocation and monitoring of budgets at a sub-national level. Debate on the role of devolved carbon budgets has bubbled along for at least eight years with both the Environmental Audit Committee and the Committee on Climate Change stopping short of recommending local carbon budgets in 2011 but emphasising that local authorities are not sufficiently incentivised or enabled to act on climate change. Organisations such as IPPR and Friends of the Earth have continued to advocate for the devolution of 5 yearly carbon budgets, suggesting they could galvanise local buy-in and drive regional ambition. Indeed the IPPR Northern Energy Strategy recommended the creation of ‘Energy for the North’, a new strategic body with overall responsibility for a northern carbon budget, which could ultimately become a statutory body, much like Transport for the North (TfN).

An approach which combines a duty to develop a Local Transformation Plan, with devolved carbon budgets and additional resources, could also help to reinvigorate both devolution and the wider UK economy. The think tank Localis recently framed the 10 years since 2009 as a ‘lost decade for the UK economy’ with their report ‘Hitting Reset – a case for local leadership’ putting forward a strengthened local state as a route to rebalancing the national economy. It makes clear how problems with our national political structures can hamstring capable local leaders, citing, for example, the fact that Sir Richard Leese, Leader of Manchester City Council since 1996 has seen 17 housing ministers and eight local government ministers since entering office.

Recent shifts in the debate on the role of spatial planning also suggest that the time might well be right to fundamentally restructure local-national relations on decarbonisation and placemaking:

- the Royal Town Planning Institute have launched a new campaign calling on the government to give local planning authorities more power to enable the UK is to meet a net zero target. As well as specific asks in relation to planning policy the campaign calls for devolved national governments and local authorities to be empowered and resourced to lead on climate change mitigation; and greater collaboration between the ministries of BEIS, DfT and HCLG.

- the Energy Systems Catapult’s work on Local Area Energy Planning points to the importance of local planning and investment co-ordination and presents a strong case to integrate carbon policy with other local planning and development objectives.

- Finally, the UK2070 Commission – established to understand the nature, extent and causes of deep-rooted inequalities in the UK – suggests that the UK lacks the long-term thinking and spatial economic plan needed to tackle inequality. The Commission stresses that tackling ‘the ‘emergency’ created by climate change and the spatial inequalities in society are inextricably inter-linked’ and proposals include the creation of four new ‘super regional’ economic development agencies who can develop place-based plans for their regions.

The ‘spatial blueprints’ proposed by the UK2070 Commission give a flavour of how an invigorated local (be that at local authority, city-region, or mega-regional level) framework for energy systems transformation could bring together many of the key challenges for communities in terms of economic development, health, accessibility, and channel them towards a decarbonised society. An associated set of maps of the four ‘mega-regions’ in England illustrate the assets the regions have and how strategic decision-making on regional development could be better coordinated across strategic housing sites, local inequalities, transport links and commuter routes, economic clusters, enterprise zones, Universities, energy, water and communications infrastructure and resources, natural assets, flood risk and climate vulnerability.

LTPs would therefore play an essential role in coordinating action both within and across governance scales – what we have referred to previously as multi-level coordination. This would not be about adding another layer to the already crowded local ‘strategy’ landscape but setting out a clear framework and monitoring approach for decarbonisation, which (1) all other strategies would need to be prepared with regard to, (2) provides a basis for regional coordination and (3) makes clear at a national level the differing opportunities and challenges for decarbonisation across GB.

The preparation of LTPs across the country would therefore also provide a route to unpick the likely regional economic and social disparities of rapid decarbonisation. Decarbonisation will inevitably progress at different rates in different places depending on the local economy, renewable resources, infrastructure, skills and so on – but we need to be able to have a frank discussion about where and why decarbonisation is succeeding or stalling in order to ensure national and local policy is aligned to support equitable and effective decarbonisation.

As both Catherine Mitchell and Matthew Lockwood have both recently argued in IGov blogs the spectrum of debate of energy and climate policy in Great Britain needs to be broadened to go beyond adversarial political debate and technocratic delegation and confront the widespread changes that need to take place in every aspect on British life. The reality of what those changes will look like – how houses will be retrofitted, the future of transport, what power technologies will dominate, what the jobs of the future will look like, how will climate risks be dealt with – all depend, to a greater or lesser degree, on the local area. We argue that formalising local energy governance structures can play a key role in both widening the debate in climate action, developing societal buy in and ensuring that the regional equity implications of decarbonisation are understood and managed.

We welcome comments and feedback on our proposals. Please email Jess Britton on j.britton@exeter.ac.uk

* This blog was updated on 29th July – Figure 1 was amended.

Related Posts

« Previous MOOC: Reflections on Emerging Energy Systems MOOC: Reflections on People, Scale and Society Next »